Education reform is a feminist issue and a racial justice issue (pt. 2)

How did desegregation lead to the dissolution of black schools, and how does it impact our teacher demographics today?

From last week’s essay on the feminization of the teacher workforce:

Measly teacher salaries and meager turnouts of educators of color across the country are negatively impacting student success. It’s well-known (and statistically supported) that good teachers lead to good outcomes for students. If we want successful students, then we need to think about education reform as a movement to reinvest in our teachers.

This week, I’m delving into part 2, where we take a look at the historic dismissal of black teachers after Brown v. The Board of Education ruled that segregated public schools were unconstitutional.

Trend 2: Public schools hired fired female black teachers because they could pay them less.

Brown is often heralded as the turning point for education equality in America. But this 1952 landmark case would wreak havoc on black schools, whose tight-knit communities had found ways to support, empower, and teach their children despite the unequal resources.

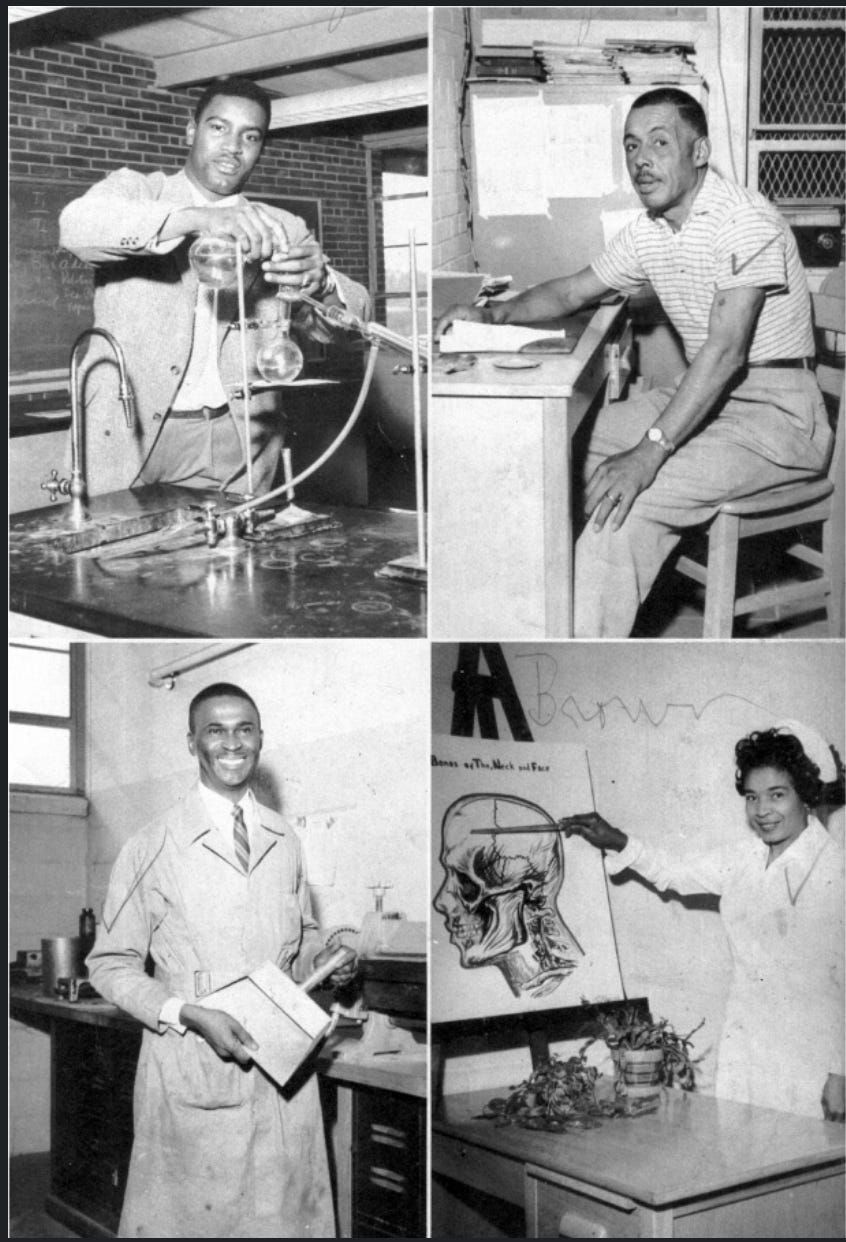

Within the segregated school systems, black schools were often the epicenter of black communities. They were a central tenet of life, with teachers who were both well-educated and well-equipped to support their students. In an interview with Malcom Gladwell on his Revisionist History podcast, Leola Brown, the widow of Oliver Brown (the lead plaintiff in Brown) described her experience at a black elementary school in Topeka, Kansas:

“We had fantastic teachers and we learned a lot…it was more like an extended family. They took an interest in you.”

This experience of being understood and academically inspired by one’s teachers was very common. In her book, Color & Character: West Charlotte High and the American Struggle over Educational Equality, historian, activist (and dear friend) Pamela Grundy, documented similar sentiments from interviewees. Schools were an extension of the communities that, despite “hard work, limited health care, and environmental hazards [that] made sickness and death regular features of life,” maintained support of one another by sharing food, caring for ill family members, gathering for weddings, funerals, picnics, fish fries, and music concerts.

“[School] gave shape to a striving community’s ambitions, becoming a space in which a corps of skilled and dedicated teachers groomed young people to rise higher and go farther than their parents ever could.”

Desegregation was, in reality, very slow to roll out. It was only after a second supreme court case in 1970, Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, that the concept of busing was established as a federally permitted solution to “further the goal of integrating public schools”.

Black parents and teachers were wary of this decision, and for good reason. An English teacher at West Charlotte High School recalled feeling “leery of being consumed. And that’s what I was afraid of. I didn’t want our people to be consumed by the white people.”

As anticipated, black students were bused out to white schools while their experienced black teachers were met with “widespread dismissal, demotion, or forced resignation” by the tens of thousands. Black schools, and sometimes entire districts, were closed down.

“Desegregation meant the end of the all-black institutions that generations of educators had shaped to fit the needs of their students and communities.” - Pamela Grundy

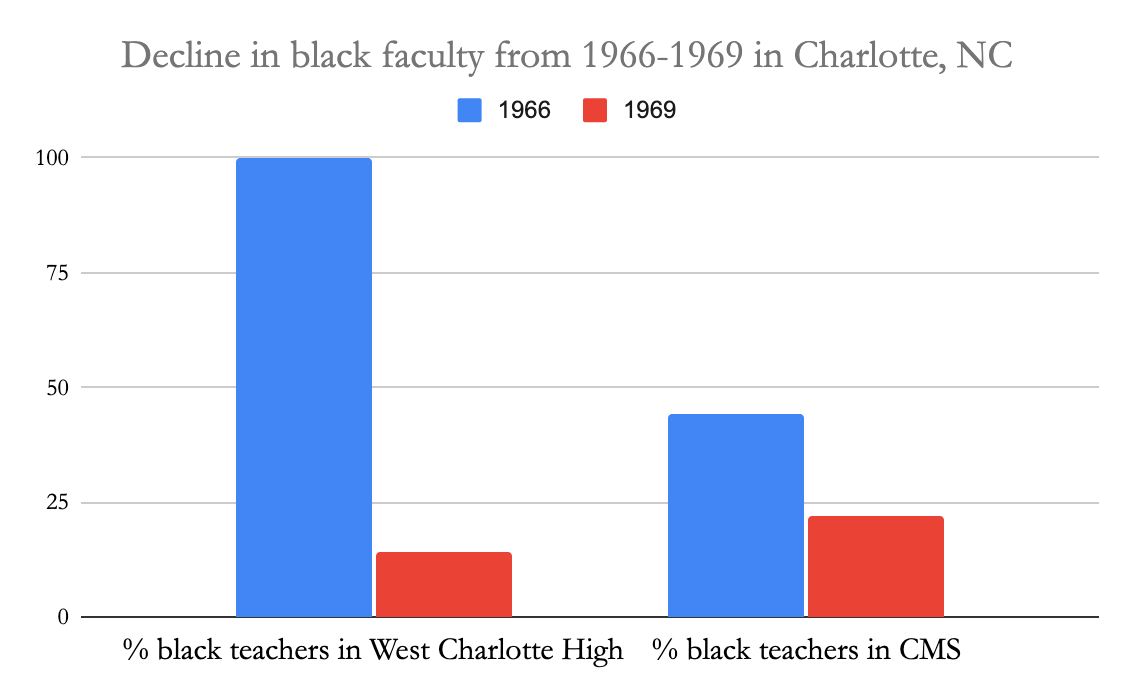

By the end of the sixties, West Charlotte High School was the only historically black school remaining in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School district. As busing went underway, 85 percent of its faculty were transferred, leaving only 19 original faculty members. Staff who were involuntarily transferred were mostly replaced with inexperienced white teachers.

In the 1968-69 school year, the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School District (CMS) hired 722 new teachers. Only 17 were black. In 1966, black teachers made up 44 percent of CMS teachers, and by 1969, that number dropped to 22 percent.

Reaganomics and “urban development” projects in the 1980s influenced the further dissolution of black communities. So, while white families fled to the suburbs, tens of thousands of black residents were displaced from their neighborhoods. Declining economic stability among black folks also led to heavier burdens on their teachers who tried to support those whose “spirits [had] been broken. Who just feel like there [was] absolutely no hope.” By 1990, West Charlotte High school had gone from being a bastion of black excellence, to a school with some of the highest poverty rates, whose faculty was now 90 percent white. Without highly experienced teachers who looked like them and understood where they were coming from, the students had little hope for finding refuge, empowerment, and deep learning in school.

Today, West Charlotte High School reports subject proficiencies that are well below district and state levels, with just 50% of students graduating with college-readiness.

That was then, what about now?

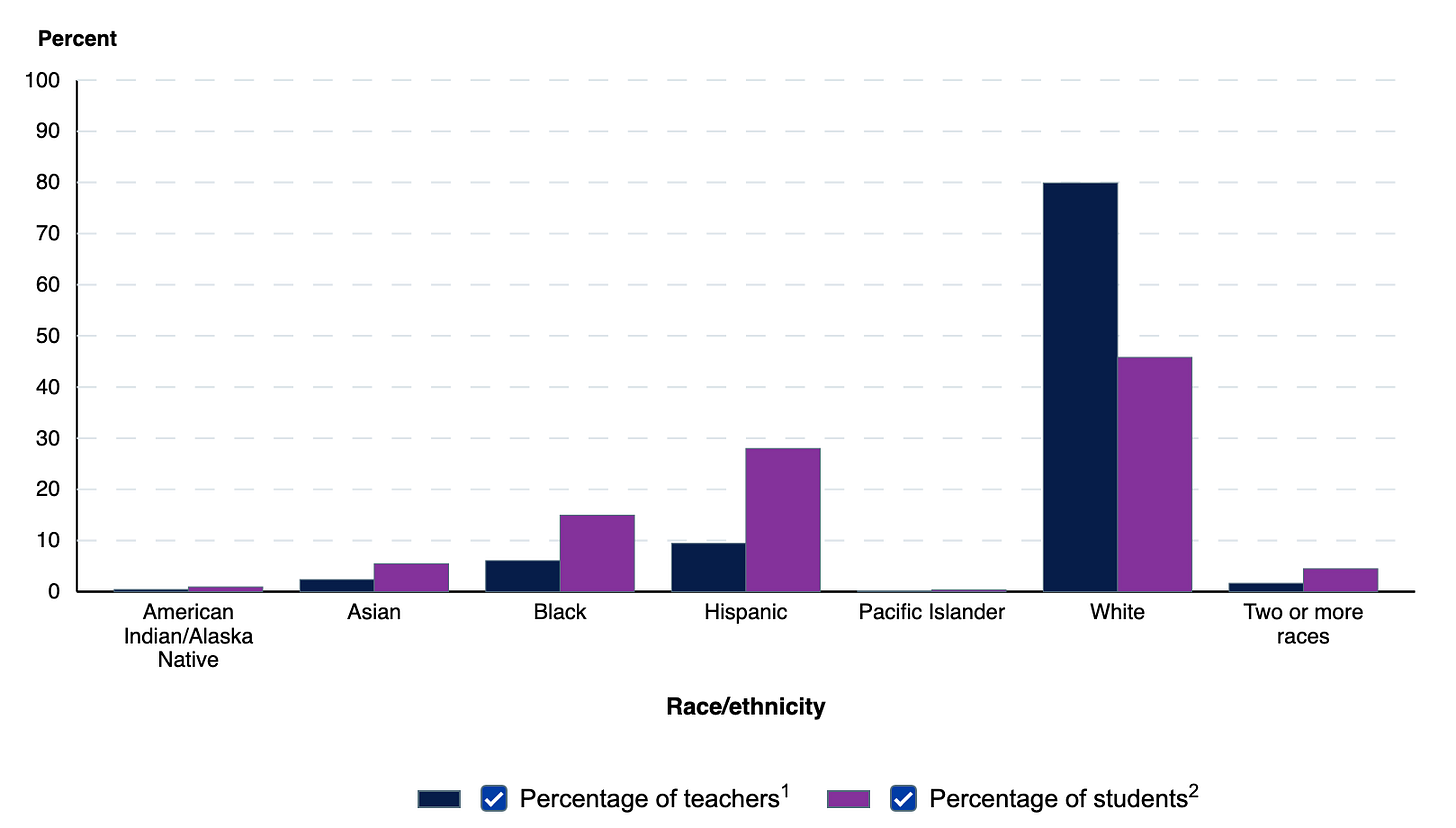

“Prior to Brown, Black principals and teachers comprised 35 percent to 50 percent of the educator workforce in the 17 states with segregated school systems. Today, no state has anywhere close to those percentages, and nationally, just 7 percent of teachers, and about 11 percent of principals, are Black” (EdWeekly)

With historical context, it’s no surprise that the demographics of our teacher workforce does not reflect the student demographic. Today, for example, 15% of students are black, while only 7% of teachers are black.

This harms black students, who are more likely to be successful in school with black teachers. With black teachers, black students have a higher chance of being placed in gifted programs. They are also less likely to be suspended, expelled, or given detention. This can be chalked up to the fact that black teachers have higher expectations for their students of color. Conversely, white teachers often harbor biases against students of color that causes them to lower their expectations for those students.

I listened to a great episode on The Weeds, in which the host, journalist Jonquilyn Hill, shared her personal experience with this phenomenon. Hill moved schools from a predominantly black school in Kansas City, where she was placed in the gifted program, to a predominantly white school in Albuquerque. At her new school, she was tested twice for the gifted program because the administrator thought her high verbal score “too high” and therefore a “false positive.” Luckily, Hill’s parents could advocate for her and reported the incident to her school.

What do we do about this?

Of course teachers can be incredibly impactful on students regardless of their identity. But in order to rectify the historic dismissal of our black teachers and the inherent harm it caused black students, we should be hyper-focused on recruiting excellent teachers of color. Students, no matter where they come from, should have access to highly qualified teachers who both understand them, and are equipped to teach them with highest standards (accompanied by a sustainable income and work environment so they can keep doing excellent work year after year).

Education reform is a feminist issue and a racial justice issue.

Illustrating the historic gender and racial biases ingrained within our education system is just the first step in determining actionable pathways towards meaningful change.

We know that persistent low teacher pay is an effect of the feminization of the workforce because women could be paid less. We know that low black teacher turnout is an effect of the mass dismissal of black teachers that resulted when white parents refused to send their children to historically black schools.

We know that low teacher pay and lacking black teacher representation is bad for kids. So, we have to start figuring out how to pay teachers more, and how to recruit more teachers of color.

Lots of nonprofits, charter schools, foundations, and think tanks are thinking about this already. The Teacher Salary Project is working to get legislation passed that advocates for national minimum teacher salaries and The Equity Project Charter has developed a financial model that allows for them to pay their New York teachers a starting salary of $140,000.

Certain medical schools are developing new tools to boost diversity in the wake of the end of affirmative action, and organizations like Forté and The Consortium for Graduate Study in Management are providing pathways for both women and people of color to pursue MBA degrees.

Can initiatives like this exist for teachers? And if so, how would they work?

That’s my homework. I’ll keep you updated.

A lot of students sometimes complain about the teacher's laziness. I know I was one of those students who disliked a teacher for their lack of passion, or even effort towards the class. As I got older, however, my perspective changed. reading this article now even further changes my perspective to sympathize with the teachers. A lack of pay, racism, and misogyny would affect the teacher's will to teach and as a result the student's results. Thank you so much for sharing this article. The first step to change is awareness. Looking forward to next week's update.