Jews for a ceasefire

When we take the time to detach ourselves from old narratives, and make space to accept and embrace different perspectives, we may find ourselves in a new place.

When we are able to be healed enough in ourselves that the other is as sacred as the self – not more sacred, but as sacred – I think we start to be able to answer the question of how to bring an end to the violence that is destroying our world and perpetuating the trauma that we are steeped in, the belief that “I can only be safe if you are imprisoned,” “I can only be safe if you are dead.” That's a trauma belief.”

Kai Cheng Thom, activist, author, and spiritual healer

The room was filled with about 500 therapists, teachers, healers, mediators, yoga instructors, and curious humans. We were gathered for a somatic trauma healing conference in San Diego. We were there to answer questions of how trauma sits within the body, how to excavate painful memories, how to tend to them, and how to use our bodies as a map to navigate the world with healing, peace, and joy. I was there to recognize my own holding patterns and my own ruptures that hadn’t been tended to. I was also there to understand my students; the ones whose inability to self-regulate sent my classroom into spirals; the ones who had endured things no child should ever have to endure; the ones who couldn’t be successful in school because of the burdens they bore every day. Without a deeper understanding of how trauma alters one’s own behavior, one cannot understand why others behave the way they do.

There was no more apt opening to a trauma healing conference. A man who was separated from his Jewish mother in Nazi-occupied Hungary as a 1 year-old stepped up to the podium. He just stood there for a moment, looking out at us. He often displays a serious comportment, but today, he was somber. He had a reservedness and a gravity about him that differed from the vivaciousness he usually possesses (despite the fact that he is 80 years-old).

Gabor Maté is a best-selling author, physician, and pioneer in holistic approaches to addiction, trauma, and adverse childhood experiences. That day, Dr. Maté began not by delivering a business-as-usual statement introducing himself or his work, but by publicly acknowledging the atrocities being committed against the people of Gaza:

“I’m checking in with myself. My heart is heavy. A hundred people were killed today trying to get some food. They were hungry. They rushed towards the trucks where the food was. They got massacred. I don't care how you feel about that politically. You can have all kinds of views about history, but this is humanity at its worst…If the teachings of the great pioneers in spirituality and trauma and health and healing mean anything at all, then we all live in the same world and we're all affected by everything that happens and we can't split ourselves and we can't split our hearts. So that’s with me, right now.”

Dr. Maté’s brave and vulnerable decision to start his talk by addressing what was happening outside our conference cocoon made me breathe a sigh of relief. Until he spoke, I hadn’t realized the pain I’d been carrying around all day, with no time to process, nor any forum in which to discuss developing news in Gaza. With Dr. Maté’s opening words, the tightness in my chest dissipated a little bit. I felt less alone.

Dr. Maté showed us what it means to be deeply connected to one’s humanity. He modeled what it looks like to recognize generational trauma and the ruptures in one’s own lived experiences, and also how to begin healing from it by extending compassion to others. He modeled what it means to separate one’s values from a belief system, and how to separate a belief system from one’s identity.

I am the great-great-granddaughter of Jewish immigrants who fled European persecution to arrive in the United States at the turn of the 20th century. Growing up, my practice of Judaism was limited to sporadic Hanukkah celebrations, seders, and rare visits to synagogue with my paternal family. I was offered the option to become a bat mitzvah and I declined, intimidated by the idea of attending more classes, learning a new language, and reading it in front of lots of people. Despite the lack of Jewish ceremony in my life, the presence of Jewish resilience, knowledge, and struggle was ever-present.

I grew up with the understanding that Jews, despite being persecuted for most of history, did have a refuge in the world. Israel was the Promised Land, the place for Jews to be safe and return to at some point in their life to pay respects to their ancestors. I went to Israel with my family in 2011 and visited Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, the kibbutzim and the Western Wall. We ate delicious food, explored markets, and swam in the Dead Sea, staring at our toes peeking out of the turquoise water as we floated on our backs. Photos from the trip depict a joyful, sunny, and culturally rich family vacation.

I had no reason to question the narrative that I was told. There was no mention of Palestine. There was no mention of the people that were expelled from their homes and killed to make room for persecuted Jews to settle. There was no mention of the current apartheid system under which Palestinians and Israelis drive with different colored license plates down different roads. There was no mention of the surveillance systems under which Palestinians live in the West Bank, or the arbitrary arrests of children as young as 12, detained with no charges and for indefinite periods of time. There was no mention of the occupation that starves Palestinians economically and literally in Gaza. There was no mention that Palestinians are shot on their property for trying to farm, or on the beach for trying to fish.

I do not hold resentment or contempt for the former narrative, but now that I know the truth — a truth that I cannot unsee — I have to question it, and even leave it behind.

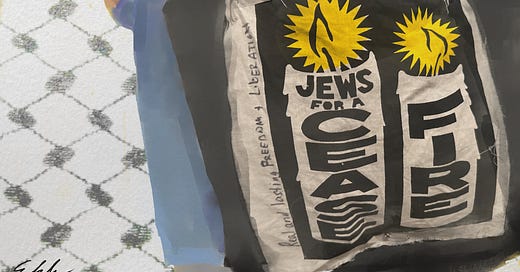

In San Diego, the day after Dr. Maté’s talk, I stood in line to enter the large conference room for our next speaker. A woman walked by me with a bag adorned with a beautiful fabric. The needlework read “Jews for Ceasefire.” I called after her: “I love your bag!”

At first, she looked back with a slightly panicked expression, as if she was calculating my gesture as a threat, and not a compliment. I briefly recoiled in embarrassment at the misunderstanding, but I pointed to her bag again. More gently this time, I repeated myself. Her face relaxed, and she walked back to thank me.

Jeannine is a San Franciscan and a Jewish mother of two. She is in a graduate program for psychology and she teaches at a synagogue in the city. “I don’t know how I ended up there, but I teach the kids all about Jewish traditions of justice and resistance. There are lots of parents who claim their kids are being bullied, but I’m there. I know that it is not happening. It’s so hurtful to witness the gaslighting and the exploitation of our traumatic history.”

As she spoke, tears welled in her eyes. There was a mutual feeling of safety, understanding, and deep pain between us. She told me that I was not alone, despite feeling ostracized from friends and family for my outspoken support of Palestinian liberation. I told her that I had been blocked by close friends, accused of sympathizing with a terrorist organization, and blamed for negatively impacting people’s mental health.

Jeannine softened and told me about the abundant community of people who feel what I feel, who are suffering from the apathy of the world around them, but who aren’t deterred and will continue to fight for Palestine. She told me about groups in the city who are working to ensure a ceasefire and Palestinian liberation every single day. We exchanged numbers and held each other for another moment before heading back into the conference hall.

At the end of the conference a few days later, I got lunch with new friends to debrief and say our good-byes. One of these new friends was Barbara, a 75-year old writer, therapist, and documentary filmmaker, whose family, through the birth of her biological daughter, comprises an intricate web of Jewish, Native and Black heritage.

When she visited the West Bank in 2022 on a trip with Palestine advocates, Barbara was reminded of the Nazi regime that terrorized her ancestors. Ironically, the people she felt most unsafe around, and threatened by, were Israelis. She left with the memory of Israeli guns pointed at her and a violent arrest.

As I sat across from her, I could see the terror of that moment reflected in her dark eyes. She described not being able to write, much less function, for months after that. As an author, a creative, and a healer, sharing stories is her passion and her way of processing her experiences. It was as if the language she knew so well was suddenly stripped from her. I asked her what led her to be able to finally write again. “It was after October 7. I just cried, and cried, emotion just flooded my body, and the words came to me.” Finally, she had reached a breaking point, and she found the words to describe what had been, up until that point, indescribable.

Our conversation was interrupted by Barbara’s phone ringing. “Oh, hold on, this is my Palestinian friend calling about our next action meeting.”

In her article, Longing for Peace and Justice, written a month after Hamas’ brutal attack and in the midst of Israel’s retaliatory destruction of Gazan civilian land and life, Barbara described her own family’s history of persecution, and the way this history inspired her to fight for justice whenever, and wherever, she can. Barbara has spent her life trying to understand how communities can both fight for justice and heal, especially among indigenous communities whose humanity and kinship has been overlooked by the colonizer’s view of them as dangerous, savage, or unruly. With this understanding of healing and resistance on a global scale, Barbara is inspired by the wisdom of Judaism that is rooted within her: its teachings, and its values.

“There is nothing Jewish, or human, about [Israel’s] response. For thousands of years, Jews have been expelled from lands, murdered mercilessly, endured forced religious conversion, and know the suffering and agony that colonialism, demonization and genocide upon a people cause. How can we justify oppression? We cannot, and many of us will not.”

Barbara’s mention of the “many of us” who will not justify oppression refers in part to the Jews who do not identify with the Zionist ideology upon which Israel was created. Barbara, along with Jeannine and Dr. Maté, have differentiated themselves from the majority of Jews who identify as Zionist. In a webinar discussion on navigating conversations about Gaza, Gabor’s son, David Maté, described the difficulty of bridging the ideological chasm in the Jewish community. As a family, the Matés were raised Zionist and identified with the movement on a deep level for many years, which David described in the webinar.

“Zionism has been an answer to a very deep question, Who am I? Who are we as a people? Where can we be safe?...Zionism has done a lot for a lot of Jewish people. And having gone to a Zionist summer camp, I can feel it inside, I can still feel the warmth and community of the Zionist dream of Jews finally liberated in this warm, beautiful Mediterranean place away from the settlers and away from the jackboots and away from the Cossacks and away from all the suffering. Finally, we're free. Finally, we're sovereign.”

From an early age, Zionism informed David’s sense of self, as it does for many Jews. So what happens when you attempt to disconnect the dream of Israel from one’s identity as a Jewish person? One’s sense of self becomes threatened. But it is possible to become unstuck from the narrative that implies one’s Jewishness can only be intact as long as the Zionist dream is fulfilled.

Barbara, Jeannine, David and Gabor have disentangled themselves while also remaining true to their Judaism. That disentanglement took years, however, and required them to employ the utmost care and intentionality in doing so. Their Jewishness is informed, but not defined by a traumatic history of persecution. Their Jewishness allows them to stand with their Palestinian brothers and sisters because they know what it is to be exiled and persecuted. It is because of their Jewishness, not in spite of it, that they can stand up for Palestinians. It is their very connection to Judaism and the values it espouses that compels them to engage in the collective call for liberation.

I am not as connected to Judaism as all of these people; I do not read Hebrew, I do not go to synagogue, I do not consistently observe Jewish holidays. So where do I fit into all of this? I question my right to speak on this issue both because I am too Jewish, and not Jewish enough. My outspokenness on behalf of the Jewish community could be read as a co-opting of a religious group to which I do not fully ascribe. My outspokenness might also suggest I do not respect my ancestors – or worse, closest friends and family with whom I share identity, love, and blood. I am betraying friends with whose family I have sat around the dinner table at Shabbat or Passover, with whom I have shared countless, loving memories.

But if I don’t act on behalf of Palestinian liberation, I am betraying myself.

I have always been a sensitive person who is easily disturbed and upset by conflict. I grew up feeling the need to right the wrongs around me, even if it was something as small as settling an argument between my elementary friends on the playground. What I didn’t always know was what to do in response to the distressed feeling. I didn’t know how to stand up to injustices, beyond just noticing they were committed and feeling that something was not quite right.

In a world where we often become disembodied, where we sever ourselves from our gut feelings, where our emotions are nothing but a distraction from productivity, it makes sense that some of us might easily tune out the events unfolding or find the topic too uncomfortable or dangerous to discuss.

But when we take the time to detach ourselves from old narratives, and make space to accept and embrace different perspectives, we may find ourselves in a new place. In this place, we might be supported by others who feel the same. We might feel lighter amidst the heaviness of the world. We might feel less alone.

“When we have the embodied knowing that the safety of the other makes us safer, that the freedom of the other makes us safer, that our freedom makes others safer and freer, that's when we are healing the rift.”

Kai Cheng Thom

Epic essay on this densely entangled situation and history. Thank you for the courage to express how I and many others feel about giving and receiving of freedom and safety.