The Education Paradox

When tasked with providing rigorous academic instruction in addition to psychological, emotional, physical, and structural support for students, our teachers are set up to fail.

This piece is adapted from its original version that I published in October 2022 on Medium. Since starting my Substack, I’ve connected with many former teachers who deeply related to what I shared in “Confessions of a recovering teacher.” These connections remind me that our stories matter, and it has inspired me to continue to reflect on my experience in the classroom and share those reflections with others. The Education Paradox is more objective, but it gets at the heart of the issues I witnessed during my time teaching. Here, I focus on the trickle-down effects of misguided education policies and failing social safety nets. Whether you’ve read it before, or are just happening upon it today, I hope you enjoy it.

“You aren’t coming here to quit are you?” my principal asked. I reassured her that I scheduled our meeting only to ask about who would fill the current vacancy for eighth grade science. The previous teacher had quit a week prior. I was in my third year of teaching — a beginner teacher still — and had just been promoted to head of the science department as a result of the vacancy. I was 24. Since the school year began, four members of staff had resigned and we had suffered the devastating loss of another. Our school was hemorrhaging, and it was only week two.

On February 2, 2021, almost a full year after closing schools due to the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper announced that the state’s public schools needed to reopen to accommodate in-person teaching. “School is important for reasons beyond academic instruction,’’ Cooper said. “School is where students learn social skills, get reliable meals, and find their voices. Teachers play an important role in keeping students safe by identifying cases of abuse, hunger, homelessness and other challenges.”

I thought of my own students : Rashaun, who ran around the cafeteria stealing packets of chips and stuffing them under his clothes; Hayley, who, despite being unhoused along with her older sister and mother, came into school with immaculate nails and braids; Paige, whose mom had threatened to kick her and her 12-year-old sister out of the house for causing trouble at home; Tayveon, whose parents refused to see how his failure in school was linked to his undiagnosed learning disability; Aria, who swallowed half a bottle of Allegra before graduation in an attempt to feel seen; Lupe, whose grandmother refused attend parent-teacher conferences because she was “done raising kids;” and Luis, who borrowed a gun in an attempt to protect his nephew and mother from his own father.

While Cooper’s appeal was meant to encourage local officials and families to support reopening classrooms, his statement illustrated America’s gross overestimation of a school’s capacity to support children. Schools are no longer considered spaces for education purposes alone. Instead, they are holding places for children whose basic needs are not being met in their communities. We have normalized the idea that one can expect their children to be mentally, socially, physically and academically cared for in the four walls of their classrooms, but teachers cannot expect to be trained or compensated for providing such service. Missing from Cooper’s speech was any mention of the school funding or the teacher training that it would require to pull off a system with such extraordinary expectations. This misguided perspective on the role that schools should play also distracts us from another pressing question: why are children’s needs not being met in the first place? Why does it fall on schools to compensate for the lack of affordable housing, accessible healthcare, job opportunities, or sustainable food options?

By perpetuating this narrative that schools are solely responsible for supporting the well-being of their students, we are making a devastating overestimation of a teacher’s capacity to do their job.

Cooper’s statement invokes the “whole child approach,” a notion that undergirds most government policy initiatives and mission statements. It suggests that education is not solely an academic endeavor, but a social-emotional one too. The term “whole child approach,” was coined when the Obama administration introduced the Common Core State Standards Initiative. This approach promoted the “critical thinking and social-emotional wellness” of all students through its implementation, and it served as a remedy for the shortcomings of the Bush administration’s No Child Left Behind (NCLB) policy.

Bush began what would become a decades-long debate about the degree to which the federal government should intervene — financially and legislatively — in the states’ education affairs. NCLB was born out of the realization towards the end of the 20th Century that the US was lagging in academic success compared with its rivals , namely, Russia, Japan and China. NCLB mandated that states issue standardized testing in Mathematics and English to all third through eighth graders, and once again in high school. The federal government would then “reward” schools with proficient standardized test scores and “punish” failing schools by cutting district funding. But since each state could create their own tests, it quickly became clear that testing standards were both arbitrary, and easily manipulated. States could design easily passable tests, thus setting low academic standards for student achievement.

This flawed and punitive framework for a crafting education policy maintained its legacy for years to come, but was not until Obama became president that the education problem was seriously revisited. In 2009, at a conference with the Department of Education, Obama introduced a new act, “Race to the Top” that would again reward states that met benchmark criteria. States had to enforce rigorous standards and assessments, provide good teachers, and turn around failing schools. The $4 billion recovery act was intended to incentivize schools to improvise. Funds would be competed for, not just “divvied up” and “handed out” to states. The first benchmark — enforcing standards and assessments — was a subtle push for states to adopt a Common Core that was under development at the time. The second benchmark — ensuring that “outstanding teachers” are leading classrooms — used data points to determine which teachers were worth keeping around and which were not. Finally, “failing schools” would be “turned around” by firing principals or staff, or converting those regular public schools into charter schools.

The messaging behind this campaign revealed an interesting irony: states would only be rewarded after they improved their education outcomes. The Obama administration was essentially saying, “come up with the solution to this problem, and then we will reward you if you succeed.” Race to the Top was analogous to rewarding someone with a pair of running shoes after they won a marathon in a pair of flip flops. To reward someone with the very thing they needed to succeed in the first place is illogical. The fact that the federal government considered “bad” teachers and inadequate testing to be the only obstacles standing in the way of student success is reductive and unreasonable.

Schools fail because they comprise of poorly paid teachers, underfunded school programs, inadequate facilities, overcrowded classrooms, and impoverished students whose academic success may be the very least of their concerns.

But a public school teacher in an disadvantaged school needn’t explain this to you — the data revealed it almost a decade later. In December 2019, statistics revealed that academic performance had not improved, nor was it even stagnant; academic performance had decreased all together. The Gold standard tool — the National Assessment of Educational Progress — reported that only one third of American fourth and eighth graders were proficient readers. Every level of students had declining reading scores over the past two years, and 20 percent of America’s 15-year-olds were not yet reading on the level of a 10-year-old. Worse yet, math and reading achievement gaps between students of color and their White peers remained. In some districts, Black students tracked an entire year behind their White peers in terms of academic achievement.

The federal government’s approach to improving scores by adapting assessment standards and firing bad teachers was met with little success because it was narrow-minded. These policies did not consider the myriad of extenuating circumstances that might cause a school — or student — to fail. In 2020, research from the Stanford Educational Opportunity Monitoring Project attributed achievement gaps not to bad schools, but to the external socioeconomic factors that put Black students at extreme disadvantages compared to their White peers. Without reconciling the enormous racial disparities that pervade all of our public institutions, any attempts to reform the education system are rendered useless.

By the fall of 2020, in the aftermath of a nationwide reckoning with America’s racist history, school districts began readjusting their missions and visions to reflect current sentiment. School leaders encouraged educators to adopt antiracist approaches, picking up on vernacular that had populated progressive conversations that summer. By the following spring, the Biden administration signed the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, a piece of legislation emblazoned with the buzz word “equity.” Equity was not a new concept in education debates, but it held more weight during the pandemic, when people of color were disproportionately impacted by the virus. Education circles therefore had to reckon with this word and what it would mean for schools to adopt more equitable frameworks.

Historically, our country relied on the concept of “equality” — not “equity” — to rectify its ties to the institution of slavery. In the Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954, the Supreme Court deemed the “separate but equal” doctrine unconstitutional. In the majority opinion, Chief Justice Warren stated, “We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of “separate but equal” has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” At this time, the word “equity” was used only in reference to “court equity,” which is the power to grant injunctions. In this opinion the word “equity” appears twice, whereas the word “equal” comes up 39 times. Over time, however, the word “equity” would take on a new meaning.

The shift in legal language demonstrated a shift in how we define fairness, as “equal” or the concept of “equality” became slowly replaced by “equity.” The report for No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 included the word “equal” 26 times, and “equity” 12 times. By 2013, the report for Race to the Top used the word “equal” only in reference to monetary calculations and the construction of spending. By 2021, the report on the American Rescue Plan used “equity” to reference the promotion of community programs and grants and the distribution of services to diverse populations. Over time, these two words and their definitions were weaved interchangeably into the fabric of major pieces of education legislation, further demonstrating America’s perplexing approach to its education problem.

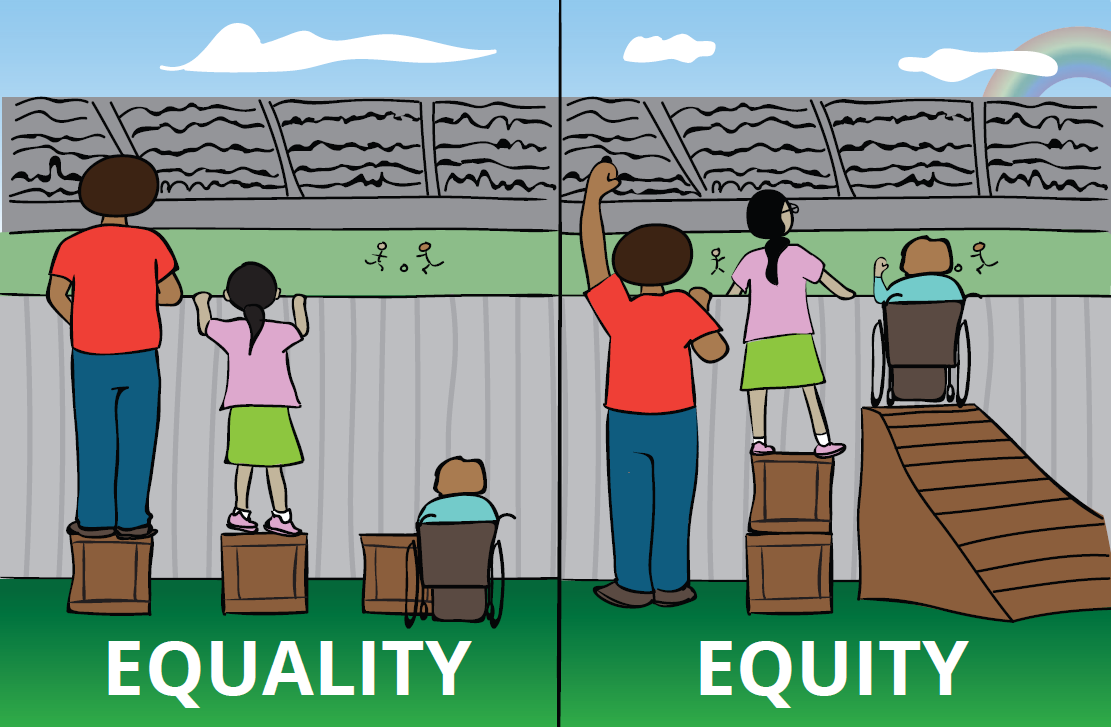

To elucidate: equality and equity are two distinct concepts. “Equality” means that everyone, regardless of background, receives the same thing. From this perspective, a fair education system provides all students with the same resources. But today, we know that not all students start in the same place, and that we must level the playing field in order for systems to be fair. We know, for instance, that students’ access to quality education can vary according to socioeconomic status. Therefore, “equity” provides us with a better framework with which to address the education problem. “Equity” acknowledges that students need varying degrees of support and that resources should be tailored to meet individual needs.

I often had to explain the key difference between “fair” and “equal” policy to my students. When they complained that it was “unfair” how some students got more chances than others, more time on a test, or more attention from me, I used the following analogy:

“Let’s pretend that all of you were my patients in the waiting room of my doctor’s office. Jayden has a broken arm, Desaun has a stomachache, and Kyla has a paper cut. I want to treat all of you equally, so I give each of you a bandaid for your troubles. Is this fair?”

I asked the room and the resounding answer is “NO!” The fair solution is the equitable one, whereby each patient receives the individual, differentiated care that they need.

But what happens if my doctor’s office only provides bandaids?

Education policies champion “equity,” yet they deny school systems the chance to provide equitable outcomes. If we laud the idea of “equity,” yet we still enforce the one-size-fits-all Common Core , are we really providing students with equitable curricula? If we promote “equity,” yet also utilize state funding models that distribute resources based on student count, are we really treating each child as an individual with specific needs? How do we build equitable schools when the policies that prescribe them are inherently unfair?

The expectations of our education system are at odds with each other. We expect that 1) all children, no matter where they live or what their circumstance, should learn the exact same skills and take the same assessments nationwide, and that 2) all children must be provided differentiated resources that nurture their critical thinking skills, their social-emotional skills, and their mental and physical health. Thus lies the great Paradox: Equality vs. Equity. You cannot have both.

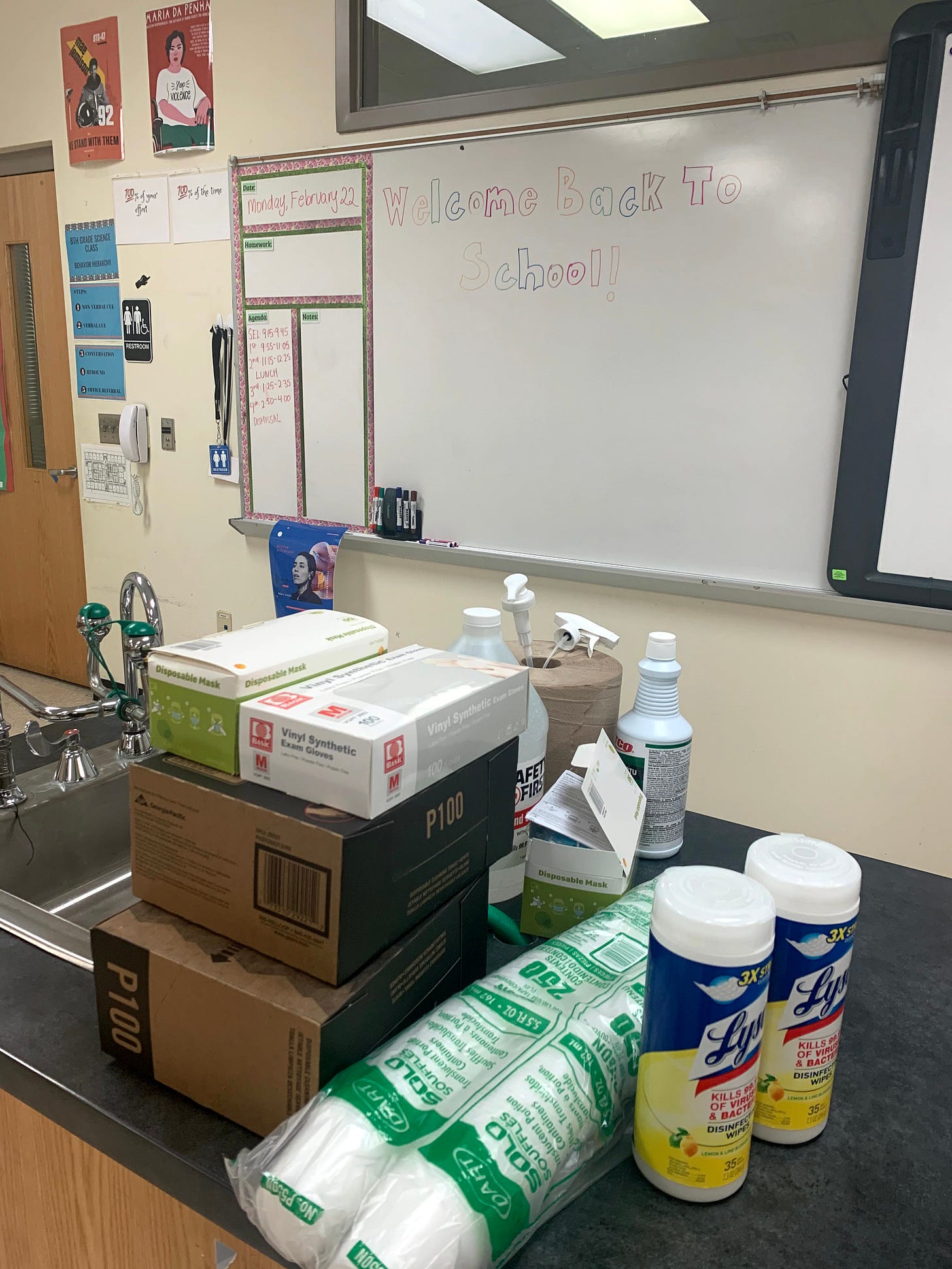

The Paradox leaves us with schools that are buckling under the pressure to provide for their students. During the throes of the pandemic, I was told I was doing “God’s work” while I attempted to teach children through a computer screen. For the most part, I was talking to a grid of black squares, with the occasional response in the zoom chat if I was lucky. Sometimes, the squares flickered to reveal Adi getting into fist fights with his sister, who was just as fed up of being crammed in a single room with several family members as he was. Other times, Billie showed up to zoom bouncing her baby sister on her knee, and Shania logged in from the grocery store with her mother. My fellow teachers and I were labeled “essential workers” but we felt as if we were quite the opposite. “Essential” work should be crucial, indispensable, but I was expected to push through my curriculum with less than a third of my students present, signaling that my work was anything but crucial. We were also labeled “heroes,” who are usually considered to be brave. Instead, teachers were written off as cowardly for opposing the hasty transitions to in-person teaching.

It is no wonder, then, that in the fall of 2021, following Roy Cooper’s announcement about the reopening of schools, Charlotte-Mecklenburg School district saw a devastating wave of teacher resignations. WCNC of Charlotte announced that over five hundred teachers left the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School district within the first month of school. Almost one hundred more had quit by December. Meanwhile, the teachers that remained dealt with the impact that COVID had on their students. Students mistrusted their teachers and their peers, socially stunted by the long period of isolation. Multiple fights broke out over what should have been petty, yet harmless, middle school drama. Teachers were met with TikTok challenges that prompted students to assault their teachers and destroy school property.

The narrative around American education is not only misguided, but also detrimental to the possibility of truly reforming our school systems. When tasked with providing rigorous academic instruction in addition to psychological, emotional, physical, and structural support, our teachers are set up to fail. And as long as we continue to fuel the idea that classrooms are the place for students’ basic needs to be met, we will continue to see the fabric of our schools disintegrate.

We have to dig deeper than throwing out progressive buzzwords and misplacing funds and competing for better scores. We cannot apply “equitable” solutions to a structure that is already deeply broken from decades of discriminatory practices and systemic oppression. If we want our schools to nurture students in a way that encourages them to advocate for themselves, to be critical thinkers and empathetic citizens, then we have to radically change our approach to education reform, not because we want to outperform our global competitors, but because we want to imagine a more hopeful future for our kids.

This is an eye-opening article, Evie. I left public education before the pandemic, so I had no idea about the low attendance rates and engagement. No wonder students lost so much ground, especially the most disadvantaged who were trapped in difficult home environments. The expectations the administration places on teachers are unreasonable even before taking into consideration students' social-emotional learning, especially considering the low pay in most districts. It's shocking but not surprising that so many qualified teachers are leaving the profession. Thank you for shedding light on this important topic.