Education reform is a feminist issue and a racial justice issue (pt. 1)

How the feminization of the teaching profession explains our inadequate teacher salaries.

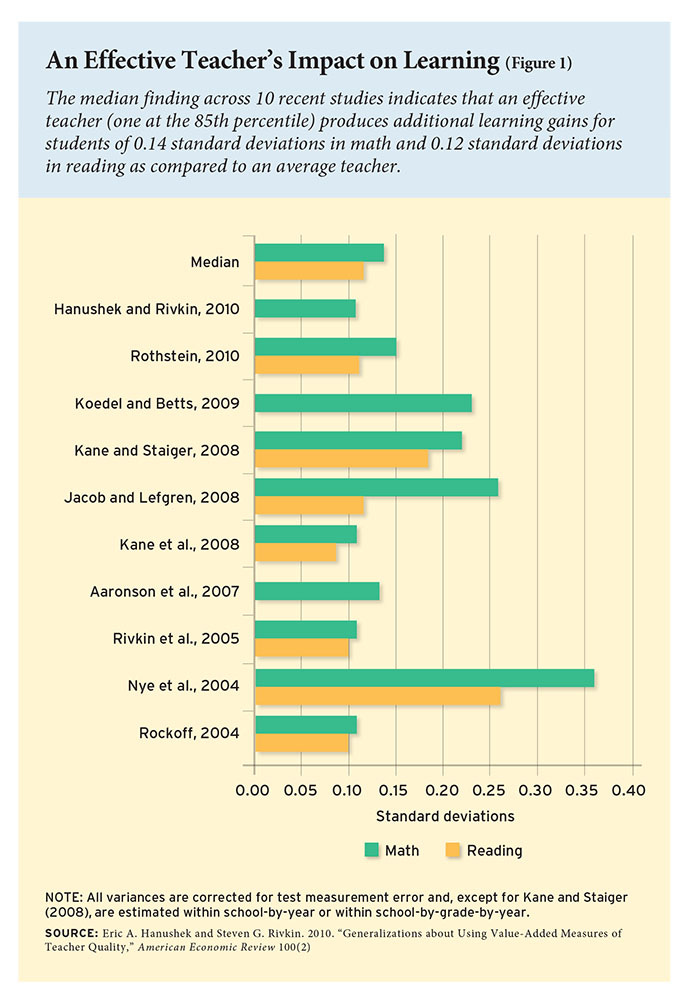

Measly teacher salaries and meager turnouts of educators of color across the country are negatively impacting student success. It’s well-known (and statistically supported) that good teachers lead to good outcomes for students. If we want successful students, then we need to think about education reform as a movement to reinvest in our teachers.

When we apply an historical lens to the development of education reform in the last century, we can see where policymakers went wrong (you can refer to my analysis of those missteps in a previous essay, The Education Paradox). But policymakers are not the only ones to blame for a dysfunctional education system. Policymakers are also not the only ones responsible for fixing the dysfunctional education system. We are too. Our own biases and prejudices influence culture, and culture influences society.

There are two historic trends that have led us to where we are now. The first trend was the influx of white women into the profession at the beginning of the 20th century. The second was the mass firing of black teachers in the late 1950s and early 60s.

Sexism and racism are not new concepts, but understanding how these ubiquitous prejudices shape the way our communities function from the schoolyard to the dinner table is crucial if we want to rectify our wrongs and establish a better future for our kids.

All this to say: education reform is a feminist issue and a racial justice issue. And, in order to become a society that is truly egalitarian, we have to start in the classroom.

Trend 1: Public schools hired female teachers because they could pay them less.

Until the early 20th century, teachers were valued members of society. Well, that’s because they were also mostly men. It wasn’t until the turn of the century that industrialization of America’s towns required a revamping of public school systems. It was also convenient that they had a whole population of literate, highly intelligent women who were not only capable of voting (shocker!) but who were also smart enough to educate the next generation (another shocker!). What’s more, public schools could get away with paying these well-read women half a man’s salary. Women were ideal candidates because they were “seen as cheap, as better teachers of young children and as more willing to conform to the bureaucratization of schooling.” Women thus became the linchpin of the teaching profession and eventually “teaching became less attractive to men.”

The feminization of the teaching profession is hardly surprising when you take a closer look at our personal lives. It turns out that the prejudices and gender dynamics that drive our education system parallel much of what is unfolding inside the home.

Eve Rodsky is a feminist and activist who defines the term “second shift” as the at-home labor women undertake in addition to their profession. This is because, “as a society, we've chosen to view men's time as if it’s finite, like diamonds, and we've chosen to view women's time as if it's infinite, like sand.” Regardless of employment status, women put in more time doing domestic work than men. The problem is that the second shift isn’t valued by the same currency as an office job. What’s more, the domestic chores aren’t getting anyone promoted. (Actually, technically men are getting dad-promos: parenthood increases men’s wages, while it lowers women’s… but that’s an argument for another time).

Rodsky developed her theory after she reached a breaking point in her own marriage, during which time she interviewed hundreds of women who were experiencing the same overwhelm as her. She compiled a 200-page spreadsheet entitled, “Shit I do,” to elucidate the amount of work that goes unnoticed at home. Much of the spreadsheet included tasks that took on a “mental load” as opposed to a physical one. The time it takes to organize pick up from day care, or plan carpools, or order snacks for the soccer team were examples. I thought about my time in the classroom, and how the endless tasks these women completed at home mirrored the unseen labor of teaching.

The bulk of a teacher's responsibilities involves creating anchor charts, wall art, birthday calendars and name cards. It’s re-doing your seating chart for the tenth time because Johanna broke up with Ty, who isn’t talking to Abi, who is in-love with Isa, who can’t work with Sofia. It’s making phone calls after dark, ordering school supplies, and fundraising for school dances. It’s picking up pencils strewn over the floor, wiping down desks with Clorox wipes, stacking your chairs, printing out worksheets, and grading papers. Not to mention, the job also requires “individuals who are brilliant pedagogues, who can also plan lessons, engage and motivate children, effectively communicate with adults, collaborate with colleagues, think on their feet, assess learning outcomes and adjust plans to accommodate new data.”

With all this said, it’s no wonder teaching it’s a female-dominated profession that pays terribly; most of the work is invisible, emotional labor that cannot be quantified. And work that cannot be quantified cannot be compensated. A teacher with over 20 years of experience will see their salary plateau at just over $70,000. In a study published by The Teacher Salary Project, teachers’ salaries did not even double over a 20 year time span, compared to other professions such as real estate, law, or medicine, whose salaries tripled, quadrupled, even quintupled.

It’s important to reiterate here that this historic analysis centers on the experiences of white, financially stable, married women. Even the household I described above — whose functioning revolved around things like soccer practice and day care – describes a household that can afford soccer practice and day care. This notion of “good mothering,” is therefore contingent on their ability to “invest vast amounts of time, money, energy, and emotional labor in mothering.”

Without financial resources, low-income mothers cannot participate in this practice of “good mothering.” An ethnographic study on the racialized stratification of motherhood noted that while motherhood is revered among middle and upper class, married, white women, “mothering done by poor, nonwhite women…is systematically devalued.” These biases further marginalize, and sometimes even criminalize, the labor of poor, black, single women in their households. These mothers’ efforts to sacrifice for their children, protect their children, and foster self-reliance — even in the absence of larger social supports — go unnoticed or simply overridden by racialized narratives. Suddenly, Rodsky’s complaints seem very minor.

The privilege of financial stability among white women that enables them to be “good mothers” is the same privilege that allowed them to pursue a profession that paid them poorly for the last century. White women could more easily move into the profession in droves at the turn of the 20th century because they could rely on their husbands to be the breadwinners. The sorry salaries just didn’t matter as much.

But this does not explain why black representation is lacking in the teacher workforce today. While the feminization of the teaching profession, the ability to pay women less, the cultural phenomenon that values women’s time as less, and the invisibility of emotional labor helps explain inadequate teacher salaries, it does not explain why the profession is overwhelmingly white.

To explain that phenomenon, we have to look back at what happened during the era of desegregation. While white women were teaching in the white schools around the country, black educators were holding down the fort in the black schools within their communities. After Brown v. Board of Education, however, everything changed.

What happens when a bigoted white parent is told their children will not only learn alongside black children, but will also be taught by a black teacher?

Read more next week…